As dean of the University of Cincinnati medical school – and a physician/researcher who helped make Cincinnati Children’s a top-tier pediatric medical center – Dr. Thomas Boat is not one to exaggerate.

So it was noteworthy that, when addressing an auditorium full of scientists at the recent “1st Midwest Symposium on Regenerative Medicine,” he opened by saying: “Today questions are being answered that in my day would have been fantasy. I stand in awe at the work that is going to be recorded here.”

And so it went. For two days, 130-plus research scientists from Cincinnati Children’s, the University of Cincinnati, Hoxworth Blood Center, Shriner’s Hospital and a handful of other institutions from around the Midwest discussed regenerative medicine. They shared successes and failures and bounced ideas off of each other.

The stakes are high. Medical problems associated with the need to regenerate tissues for lungs, hearts or the nervous and musculoskeletal systems lead to immeasurable human suffering and cost the U.S. economy hundreds of billions of dollars annually. Heart disease alone costs $108 billion. The research process is complex, time-consuming and expensive. And in today’s economic and political climate, the current funding environment for life sciences research is somewhat uncertain.

The idea for the symposium came from Dr. Ronald Sacher, director of Hoxworth. Given the busy and intensely focused work lives of research scientists, Sacher said disciplinary silos can form and undermine the sharing and collaboration that foster new ideas.

Indeed, several scientists attending the symposium said they had been unaware of recent progress made by colleagues just a few floors from their own labs. So in predictable fashion for a room full of inquisitive scientists, sidebar conversations became a common sight.

The 30 or so presentations covered the human body from head to toe, and possible therapeutic approaches from cell manipulation, reprogramming and genetic therapies. At one point someone suggested that in the future, fixing the human body might not be all that different from keeping one’s car on the road. If a part breaks or is defective, just replace it.

Using animal models – like frogs, flies and fish – scientists are figuring out what genes and biological processes cause organ systems to form. That knowledge becomes the basis for experiments on mouse models and human cells to figure out the biological recipes needed to repair or regenerate defective cells and tissues.

Imagination and innovation are combining with scientific process to produce results. Scientists spoke enthusiastically – and realistically – about varying degrees of success to regenerate lung tissues that could become transplantable grafts for infants with underdeveloped lungs, or biological patches that might mend broken hearts.

One can’t help but wonder what new realities may be on tap for next year’s symposium.

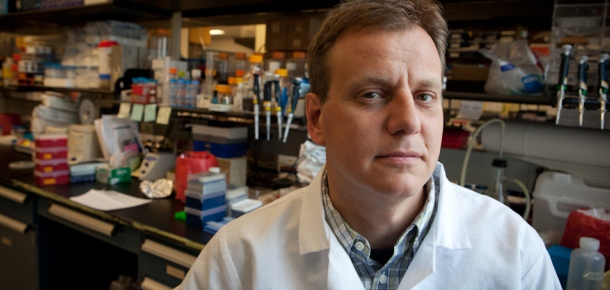

Learn about one of the projects presented at the symposium by Cincinnati Children’s researcher Dr. Harmut Geiger (pictured above), who may have discovered a way to reverse cell aging.