As both a pediatric surgeon and a researcher, I have dedicated my career to caring for and investigating potential therapies for patients with intestinal failure.

Even though we have been studying the human intestine for decades, there is so much we don’t know about it.

Major gaps in our knowledge about the human intestine mean we also lack an understanding of what causes human intestinal diseases. This has impeded our ability to find the most effective treatments, grow the organ for study or – perhaps one day – generate tissue as a possible replacement therapy.

This is crucial for children who suffer from gastrointestinal disorders that need more optimal treatment strategies – in particular conditions like Crohn’s diseases or short bowel syndrome.

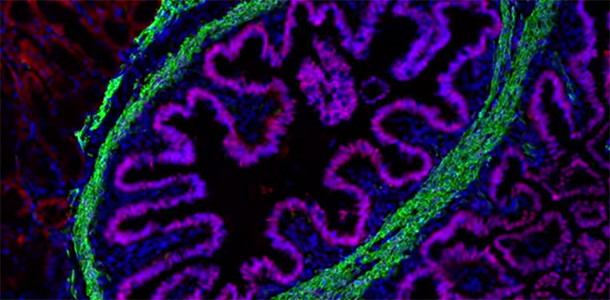

But the intestine is incredibly complex and the idea of actually growing one seems impossible, right? The organ consists of a rapidly renewing mucous membrane organized into finger like projections, which line a functional muscular tube.

Fortunately, what once seemed undoable has entered the realm of the possible, in no small part because of the efforts of researchers here at Cincinnati Children’s. The earliest methods to culture – and grow – human intestine were reported by scientists here in 2011 in a study published by Nature. Our researchers named the tissue Human Intestinal Organoids (HIOs).

These HIOs were grown in the lab from pluripotent stem cells – which can become any cell type in the body – in a dish.

This major advancement provided important insight into the development of the bowel, but it still did not provide functional intestinal tissue that could further our understanding human disease. Nor did it offer a clear method to provide tissue for regenerative medical approaches.

Which leads me to our most recent work, which was just published in Nature Medicine yesterday. My research team demonstrated that transplanting HIOs made from patient specific cells results in the development of functional intestinal tissue. In other words, we successfully transplanted “organoids” of functioning human intestinal tissue into mice, creating an unprecedented model for studying diseases of the intestine.

This study also supports the concept that patient-specific cells (those donated by individual patients) can be used to grow intestine, which provides a robust and meaningful way for us to study human-specific diseases. It also supports the concept that growing human intestine is possible for future regenerative medicine to replace human bowel.

You can learn more about what this breakthrough means for patients with intestinal disease in the following video:

My son, Trent Kissick, is a short-gut patient of Dr. Samuel Kocosis…Is there more extensive information on this? This brought me to tears! This would be so amazing for Trent. Do they know about medicine absorption in the newly grown intestines? Is it as functional? Oh so many questions….Is there anymore literature on this beside what I’ve just read???