My son, James Dickson, was born with tetralogy of Fallot, a congenital heart condition comprised of four heart defects which cause oxygen-poor blood to flow from the heart to the rest of the body. He was only eight months old when he had his first heart surgery. He was almost ten when he had his second.

James was twelve and a half years old when a routine cardiology checkup discovered growth on his replaced pulmonary valve. After blood tests confirmed the presence of bacteria, he was diagnosed with endocarditis and was admitted to Cincinnati Children’s CICU in January 2015 to start IV antibiotics.

He spent a week at Cincinnati Children’s before being discharged with a PICC line so his antibiotic regimen could continue at home. James was also there for a week in April for surgery to replace his pulmonary valve. Although the bacteria were removed from his heart during this surgery, his blood work continued to concern his doctors, and he remained on antibiotics until the end of May. I had the below thoughts as the antibiotics came to an end.

Surrealism, PICC Style

The day the doctors told me they were going to pull our son’s PICC line, the world became very surreal. He had been on IV antibiotics for more than four months, fighting the bacteria that had invaded his heart and grown, causing havoc we had never dreamed of. Every time we reached the goal date, the bloodwork results caused the finish line to be moved—six weeks, then surgery day, then a week after surgery, then another week, then six weeks after surgery…no, now tack on a few more days until the office visit…. We knew from the outset that they were just estimates. No one, including the doctors, imagined that a six weeks antibiotics therapy would turn into nineteen weeks to the day.

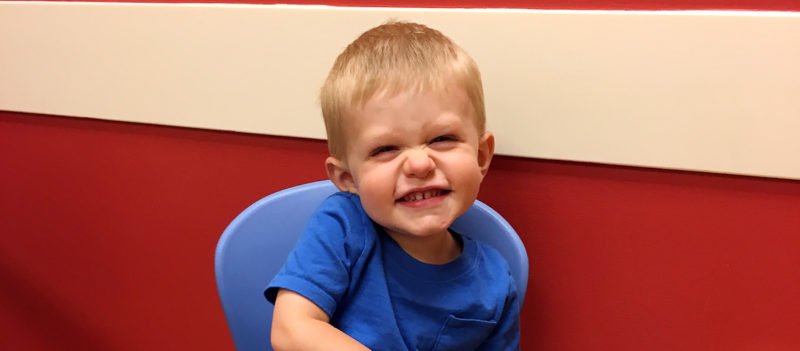

His body had been fighting the infection almost silently before it was found in a routine yearly checkup. He tolerated the regimen well, took exceptional care of his PICC dressing, was cheerful and willing every twelve hours to be hooked up to the pump and have the concoction flow into his veins. He ate breakfast on a tray during his morning dose, and many times deciphered math homework on a lap board amidst the evening one. He cooperated with the twice-weekly nurses, holding breathtakingly still while they dealt with sterile dressings and cap changes, being brave at needle sticks when the PICC line would not draw blood for labs.

The doctors and nurses who engineered and executed his care did so consistently with empathy and professionalism. Some were his champions, and to them we are forever grateful. The nineteen weeks are piffle compared with what could have been, and we have our guy, safe, and his health is righting itself, heading in the correct direction.

So the day it ended, the day they said it’s all over, he can be untethered… The world honestly became surreal for me. A little skewed, almost like someone hit the 3D button on the Nintendo and the screen is cockeyed. There’s a silent humming, a shimmer in the cosmos, like the air on a stifling hot day, only it isn’t hot.

It will right itself soon, I imagine, for unreality has no consistency, and the fabric of the world will reknit and become stable again. But for today, I am a little stunned.

It was not, in retrospect, like a tunnel. There was no claustrophobia, no light to reach, no rumbling or rushing or sense of stagnation. There was a very low day, at about six weeks, when we were told the end was a no-go, and he needed the antibiotics until the surgery that would replace his pulmonary valve. Molasses, quicksand about our feet, “say it ain’t so,” colored that day.

But then, it became the reality. Life was alarms and antibiotics and flushing the line while counting so you go slow enough and don’t let the ends of the syringes touch anything until they’re connected and washing washing washing your hands. Encase his arm in cling wrap and tape so it won’t get wet, pass him off to husband for the shower. Keep track of supplies, order from the pharmacy, take his temperature daily. It was the norm.

And now, they say, it is all over. Stop antibiotics today, tomorrow we’ll send a nurse to take it out. Just like that, the immediate imperative is taken away. Poof.

Tomorrow, Saturday, I expect to sleep in a little. No wakeup buzzer for the first time in 133 days! He will be up at the crack of dawn regardless, playing with Legos, getting out a yogurt. I also expect we will be celebratory—“the nurse comes to take it out today!” will be joyously exclaimed. And when it is out for good, when the medical supplies have left his bedroom and his desk is his own again, the new reality will begin to form. When we look back, when we tell this story again, one thing I know:

We will be grateful.

James has been in our thoughts and prayers. We had a son who had a lot of problems as a youngster, so we can have an idea of what ya’ll have been through these past months. Sandra and Linda taught together at WCHS years past. God Bless