“What’s this rash,” I asked our local pediatrician in Oklahoma as he was finishing my son Jonathan’s two-month check-up. There were a few small, scaly bumps on his back that wouldn’t go away. It looked odd, but babies get rashes so I was expecting it would be a simple answer.

Instead, it was the start of a tortuous journey that would include chemotherapy and traveling almost 900 miles for a life-saving liver transplant.

Diagnosis: Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

His doctor referred Jonathan to a dermatologist, who wanted to biopsy the rash to rule out a very rare disease called Langerhans cell histiocytosis, known as LCH for short. To everyone’s surprise, it came back positive. In infants like Jonathan, LCH is usually either a harmless skin rash that goes away or a potentially life-threatening disease that causes lesions in internal organs and requires chemotherapy. We were relieved to find out that further tests showed the LCH was only in his skin. However, he would need close monitoring to make sure it did not show up anywhere else.

Shortly before his first birthday, we found out that the LCH had spread to his bones, liver and spleen. Without chemotherapy, the LCH would cause more damage to these organs and be fatal. Over the next few weeks, the LCH took off aggressively. The chemotherapy wasn’t working and he was getting very sick with daily fevers. His doctors switched him to a stronger chemotherapy. Despite the harsher side effects, we could see it working on the scans. We were finally getting ahead of this beast!

Complications with the Chemotherapy

We did not celebrate for long. The next week, Jonathan was hospitalized because of a severe complication. His liver had been damaged by the LCH and now the chemotherapy was causing more damage. After consulting with several doctors, including Dr. Kumar at Cincinnati Children’s, his doctors decided to switch Jonathan to newer oral targeted therapy called dabrafenib that would more precisely target the gene mutation that was driving the LCH. The next scan showed no sign of LCH. While this was great news, there was still uncertainty on how his liver would hold up over time.

In early 2018, we learned that Jonathan’s damaged liver had caused swollen veins to develop in his esophagus and stomach that were at risk for bleeding. If they bled, it could be catastrophic. He would need a liver transplant. We were referred to a children’s hospital in Texas to complete a transplant evaluation. Several weeks later, we were told that he was denied a liver transplant because of the LCH. It was devastating news.

Jonathan Gets A New Liver

His doctors immediately recommended that we get a second opinion at Cincinnati Children’s. There, we met with Dr. Adam Nelson with the LCH team and Dr. Alex Miethke with the liver team. When we returned back to Oklahoma, Jonathan’s liver started to deteriorate faster than anyone anticipated. He had two bleeds a few weeks apart. During the last bleed, he lost a significant amount of blood and required substantial blood transfusions. He was placed in the pediatric intensive care unit to manage the bleeding. When he was stable enough to transport, he was flown from Oklahoma to Cincinnati Children’s to await a liver transplant. On July 11, 2018, Jonathan went into surgery to receive a new liver. We are incredibly appreciative of the donor family who gave him the gift of life.

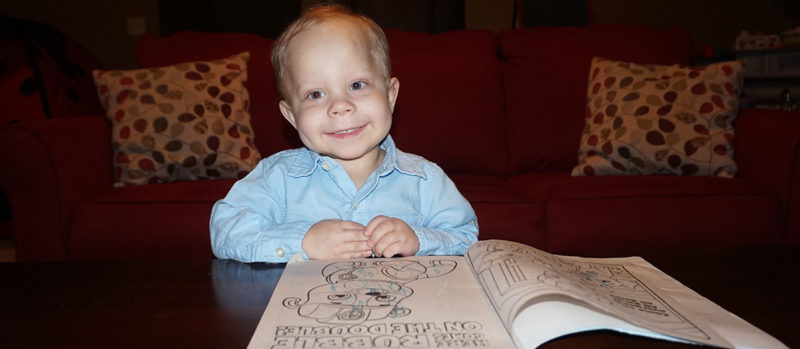

It has been seven months since the liver transplant and Jonathan is doing terrific. The transformation has been dramatic. Before the transplant, he had difficulty walking because of how large and damaged his liver had become. Now, he is running and playing with ease. After over a year with a feeding tube, he is back to eating on his own. His skin and eyes no longer have a yellow tint. He is full of life and energy.

Jonathan’s New Regimen

Jonathan continues to take dabrafenib for the LCH and anti-rejection medicine for the liver transplant, but otherwise is a normal two and a half year old boy. Prior to a few years ago, children who had chemotherapy-resistant LCH had to endure more intensive treatments with higher toxicities or suffer further damage from the LCH, both of which could be fatal.

The discovery of the BRAF gene mutation in over half of LCH tumors and the development of drugs which target this same mutation have been revolutionary in the treatment of this very high risk group. By taking a medicine at home, children have had their aggressive LCH go into remission with no or minimal side effects. Jonathan’s situation was further complicated by the critical need for a liver transplant. Cincinnati Children’s research and experience with using dabrafenib for LCH was a game changer that allowed Jonathan to receive a life-saving liver transplant.

We are incredibly appreciative of the excellent care Jonathan has received. He had a wonderful group of doctors and supporting staff who genuinely care about him and have helped him get back to being our silly boy with deep belly laughs and huge smile.

To learn more about our Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Center, please call 513-517-CBDI or email us at lch@cchmc.org.